This post was a precursor to Casey's book "Debugging Your Brain."

Modeling The Brain

You are about to learn how to “debug your brain”, making yourself happier and more effective. You’ll end up with a systems-thinking way to view yourself, a mental model of your mind.

“Debugging Your Brain” is a 5-part series. Part 5 is still in progress and is not posted yet.

- “Part 1: Modeling” - When brain-debugging helps, and a model of how the brain works when debugging.

- “Part 2: Breakpoints” - How to get your mind into a state where you can debug: how to hit a breakpoint. Here you’ll investigate what the “inputs” to your system are.

- “Part 3: Processing Experiences” - Six concrete ways to deal with processing experiences more fully and effectively.

- “Part 4: Validation and Close Relationships” - How to effectively validate and support close friends.

- “Part 5: Thoughts” - You’ll learn about the 10 most common “maladaptive thought patterns” you’ll want to look out for and convert into “adaptive” thought patterns.

I assign “homework” at the end of some sections – you’ll learn the most if you actually do these.

Who’s writing this? Hi, I’m Casey! I studied neurobiology at Yale University. I am a co-author on a few neurobiology papers. I have also worked in software development for 10 years.

Goals

Do you want to be a happier and more effective person? Of course you do!

The following “brain debugging” techniques will help you choose the best response in a given situation, to get the most effective outcome. One of the worst (least adaptive) outcomes is ending up in a “downward spiral”. The following techniques are especially important in high-stakes or emotional situations where you might a “downward spiral”.

These will help you understand yourself better, they will help you communicate your mental state more clearly, and they will help you understand other people better as well. It can even help you understand other people’s perspectives more readily and quickly.

When you are on autopilot in a stressful situation, you may end up with an undesirable outcome. You might not convey your ideas clearly, and you might damage your relationship with the people involved.

When can you apply these techniques? Either in the moment it’s happening, if you catch yourself, or after the fact when you can reflect back on the situation. You might be able to change the outcome of the current situation, or you might at least set yourself up to have a more desirable outcome if a similar situation arises in the future.

Opportunities

Here are three examples of situations where “brain debugging” may help. Each of these bad situations might end up with a desirable or undesirable outcome. Later we’ll get into what you might do to make yourself more effective in each of these, getting a more desirable outcome.

Work Disagreement

Let’s say you’re at work and you have an idea, and your coworker has a different idea. You don’t agree. You’re having an argument, and it gets heated. You both believe very strongly that your idea is the best one for the situation. Hopefully your team will end up making the choice that’s best for the situation. This topic will likely come up again – what can you do better next time?

Leaving The Door Open

Imagine you’re a parent, and your kids forgot to shut the front door – again! You snap at them. You later feel guilty for snapping. It wasn’t the most effective way to change their behavior in the future, and they got upset right back at you. You know you could have done something differently, but it was hard to in the moment.

Hangry Meetup

Once I (Casey) was headed to a meet-up. I hadn’t eaten dinner yet and I found out there was going to be NO PIZZA at that meet-up. It was raining. I stepped in a puddle. I thought to myself “everything is the worst”. All of a sudden I couldn’t imagine going to the Meetup anymore – and that would have been a shame, because I was really looking forward to it. I managed to catch myself, and I corrected this in the moment. I told myself that my wet/hungry state could both easily be fixed, and I convinced myself to go. I’m glad I did!

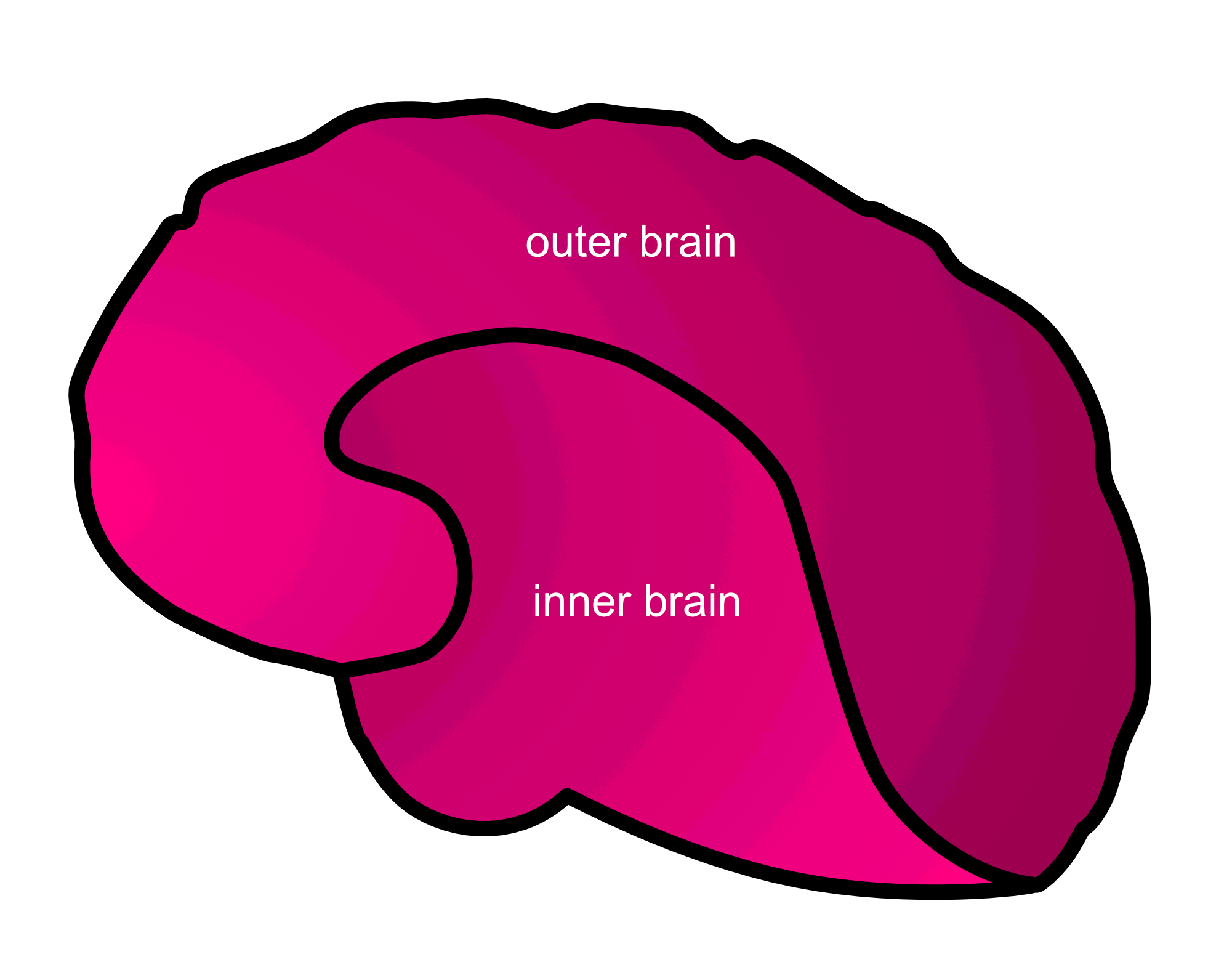

Inner vs Outer Brain

Some believe that “left-brained” people are more inclined to be creative, and “right-brained” people are more inclined to be analytical. Analytical vs creative may be a useful dichotomy, but these traits don’t seem to stem from the two hemispheres of the brain. The difference between these two halves of the brain is often exaggerated. Here is one study that goes into this in some depth.

A much more useful dichotomy is the inner brain versus the outer brain. Let’s illustrate the difference between these two halves.

You can see the difference in the two paths with this example with cats:

A cat by its cat-food bowl turns around, sees a cucumber on the ground, and then jumps in fear. The cat likely realizes it’s just a cucumber moments later

A cat by its cat-food bowl turns around, sees a cucumber on the ground, and then jumps in fear. The cat likely realizes it’s just a cucumber moments later

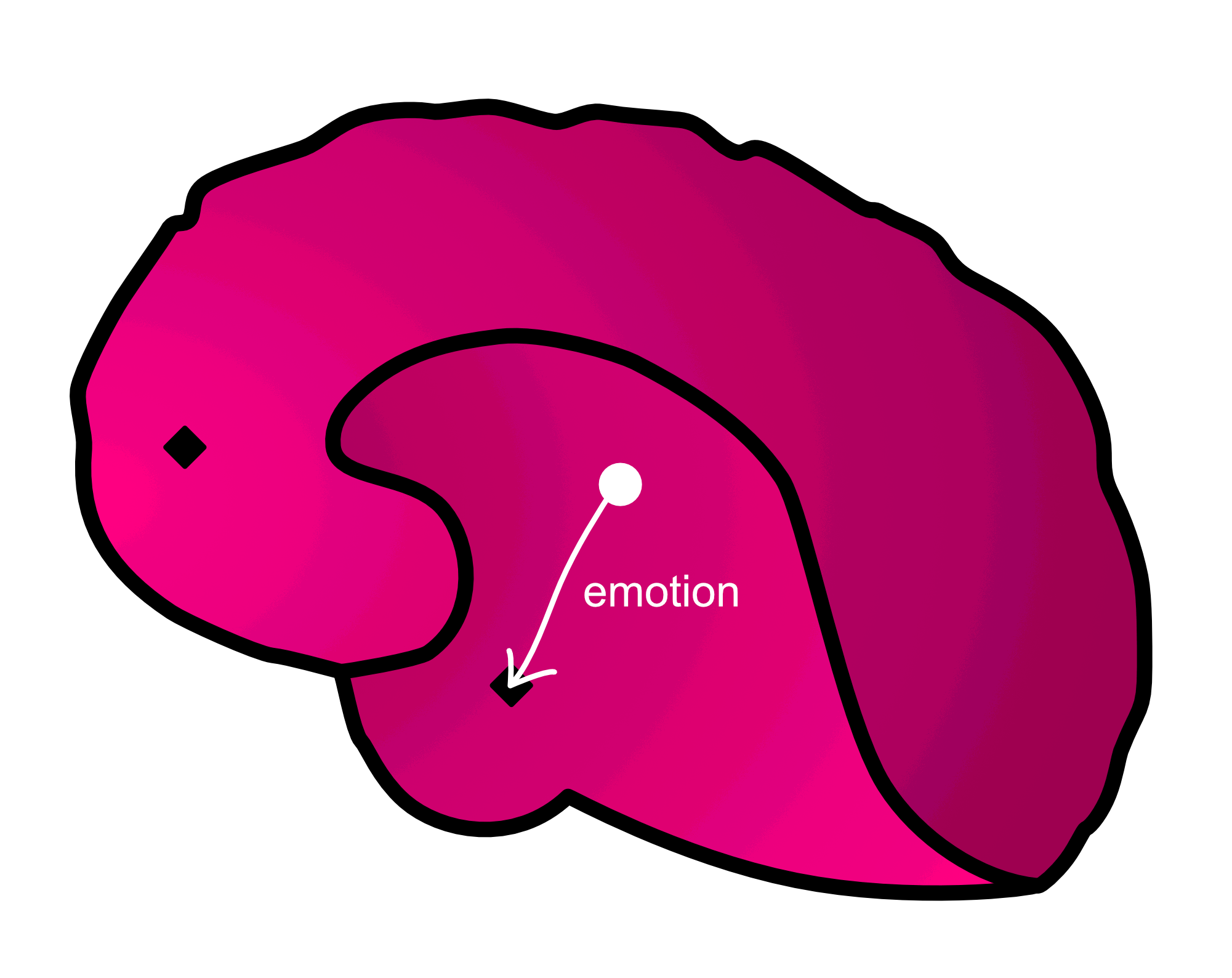

This illustrates the “Dual Pathway Model of Fear” (LeDoux). I’m using fear here as a vivid example, but the core idea applies to non-fear emotions as well.

The “low road” path is much faster than the “high road” one. The low road processes emotions very quickly, on the scale of milliseconds. It only has to go through the “inner brain” (Limbic System), which is a much shorter path. Humans and animals both have this part of the brain. It is older than the “outer brain” in evolutionary terms. The inner brain is where fear is experienced.

The “inner brain” or “low road” pathway is shorter and faster.

The “inner brain” or “low road” pathway is shorter and faster.

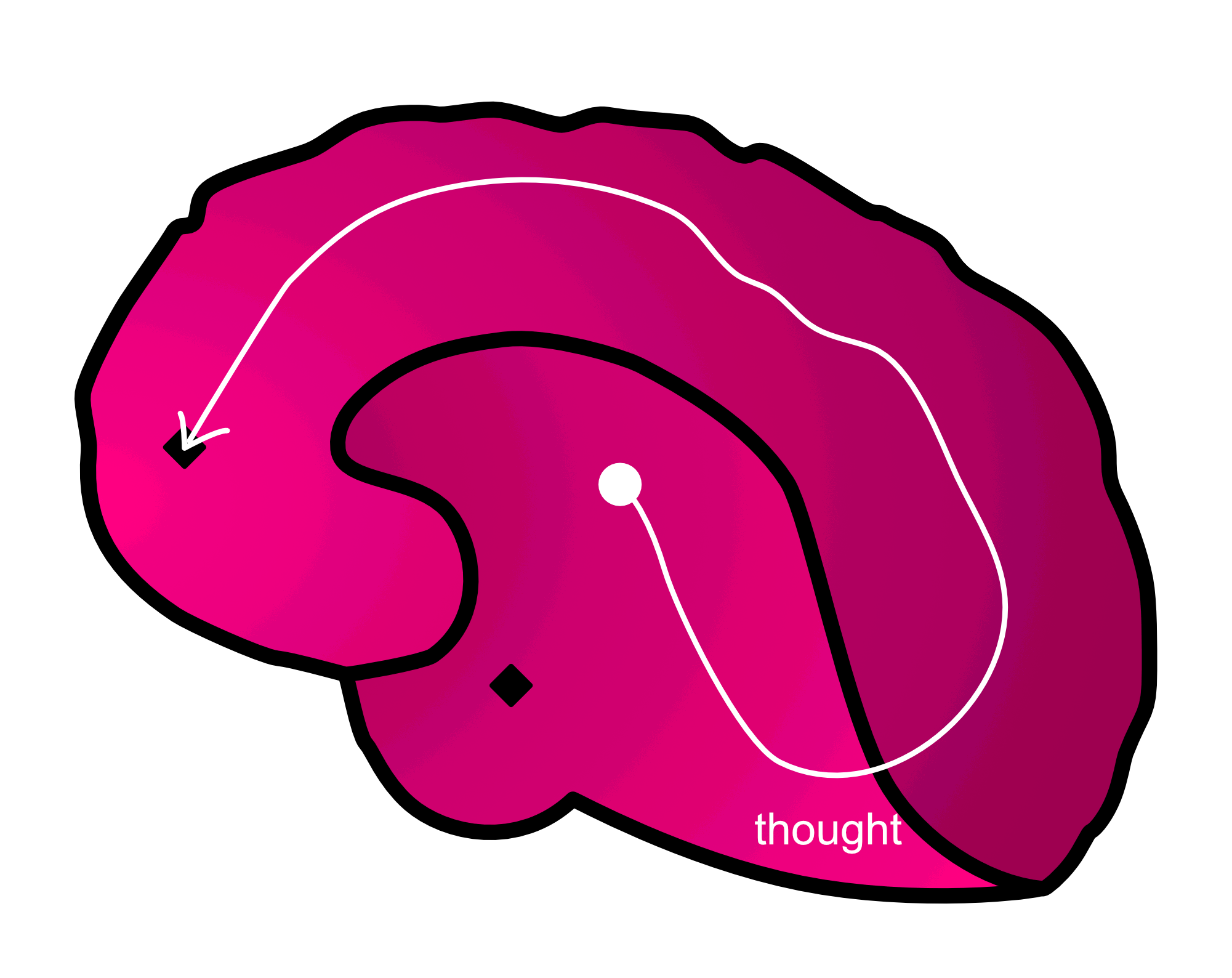

The “high road” is much slower. Thoughts are processed more slowly, on the scale of seconds. It has to go all the way through the “outer brain” (cortex), which is a much longer path. The cortex is the part of the brain humans actually think in – your conscious mind. Humans have the largest cortex relative to brain size – much larger than animals. Some people like to oversimplify and claim that animals can’t “think” – that they don’t use their cortex in the same way humans do.

The “outer brain” or “high road” pathway is longer and slower.

The “outer brain” or “high road” pathway is longer and slower.

| “low road” | “high road” |

|---|---|

| “inner brain” | “outer brain” |

| Limbic System | Cortex |

| faster (~ms) | slower (~s) |

| Feelings | Thoughts |

To summarize, “inner brain” feelings are processed much more quickly than “outer brain” thoughts are. We tend to “feel first, think second.”

Systems Thinking

IPO Model

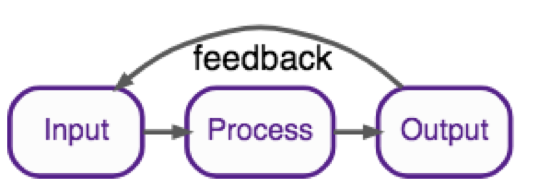

Developers, engineers, and scientists are great systems thinkers. Whether or not you identify with any of these, you can be a systems thinker too! Let’s break down one of the most common and simplest systems models, the “IPO” Model.

The IPO Model

The IPO Model

IPO stands for “Input, Process, Output”. The IPO Model has input, output, process in the middle, and sometimes it includes a feedback loop.

A textbook example of the IPO Model is the thermostat in your home. The thermostat measures the temperature of the room (input). It then compares that temperature to the set temperature, determining if it’s above or below the temperature you set (process). It then toggles the heater on or off accordingly (output). The temperature of the room changes, and eventually the cycle repeats (feedback loop).

I learned about this model in a middle school “engineering” class, and it was my first exposure to systems thinking. I nicknamed this simple model “The Engineer’s System Diagram” at the time, and only later learned to call it the IPO Model.

You can apply the IPO model to software development – it maps pretty cleanly to a function. A function accepts arguments (the input) and returns a return value (the output). Some code happens inside the body of the function (the process). Calling the function also affects other things in the software, which sometimes calls the function again (the feedback loop).

Systems Thinking & Conscious Thought

We can use the IPO model to model brains, too!

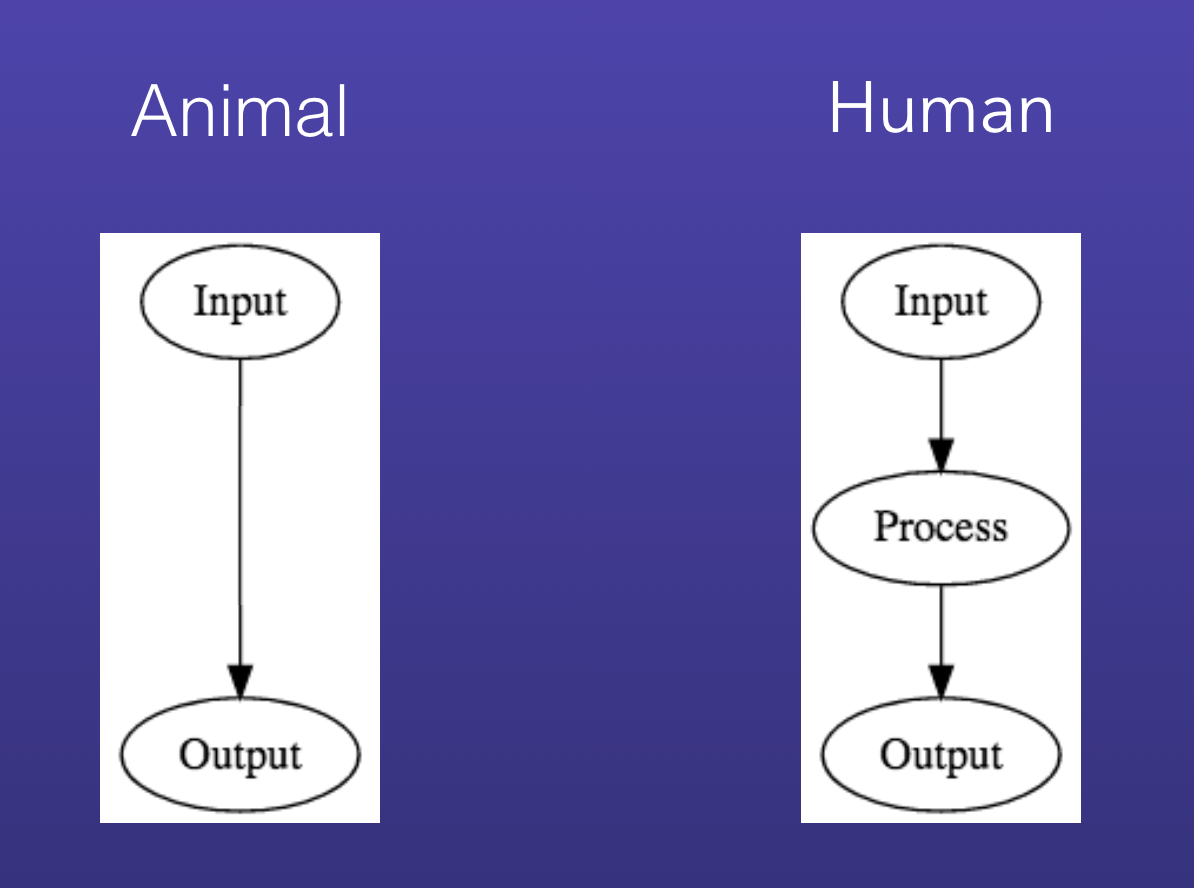

The simplest form of this diagram is just input and output. Imagine a simple model of an animal that says they don’t really “think” – they just respond to their environment.

The classic “Pavlov’s Dog” idea uses this model. The dog is trained to associate a bell being rung with being fed. After this conditioning, every time the bell rings, the dog salivates – even if there is no food around. The dog doesn’t have to decide whether to salivate. Salivation just an automatic reaction it has to external stimuli. This phenomenon can be referred to as “Pavlovian conditioning” or “classical conditioning”.

In an oversimplification, we can imagine that there is no conscious “process” going on inside the animal. In contrast, we believe we humans always have conscious thought – we think thoughts and feel feelings in a conscious way.

Model of an animal: input leads to output. Model of a human: input leads to process leads to output.

Model of an animal: input leads to output. Model of a human: input leads to process leads to output.

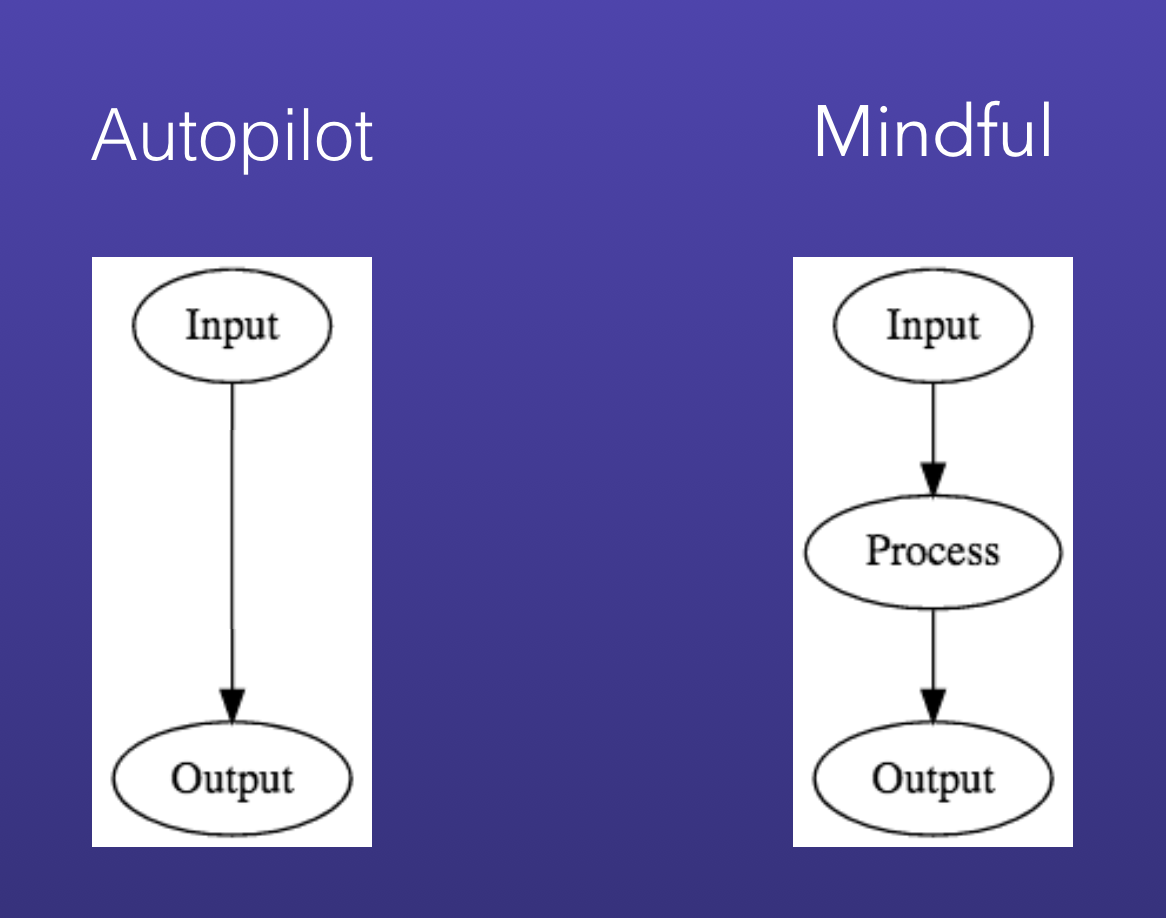

But we humans aren’t always so aware of what’s going on inside our heads. When we’re on autopilot, the “animal” model we just discussed (no process step) seems more appropriate. On the other hand, when we’re more mindful that’s when we’re consciously aware of our thoughts and feelings. When mindful, we have more control/influence over the “process” part of this system.

Model of autopilot: input leads to output. Model of mindfulness: input leads to process leads to output.

Model of autopilot: input leads to output. Model of mindfulness: input leads to process leads to output.

Automatic vs Deliberate Thoughts and Feelings

You experience both “automatic thoughts” and “automatic feelings” – they both just happen “to” you. From the perspective of your consciousness, they’re inputs that you can’t control.

When you are being “mindful” you can then actively choose to have “deliberate thoughts” and influence your feelings. You can probably imagine how to have a “deliberate thought” – you just think it!

As for feelings, you can’t will yourself to experience a specific feeling directly. You can, however influence your feelings based on the deliberate thoughts you think. This influenced-feeling is partially deliberate. This is partially within your influence, but not within your (direct) control.

| automatic | deliberate | |

|---|---|---|

| thought | automatic thought | deliberate thought |

| feeling | automatic feeling | influenced feeling |

Downward Spiral

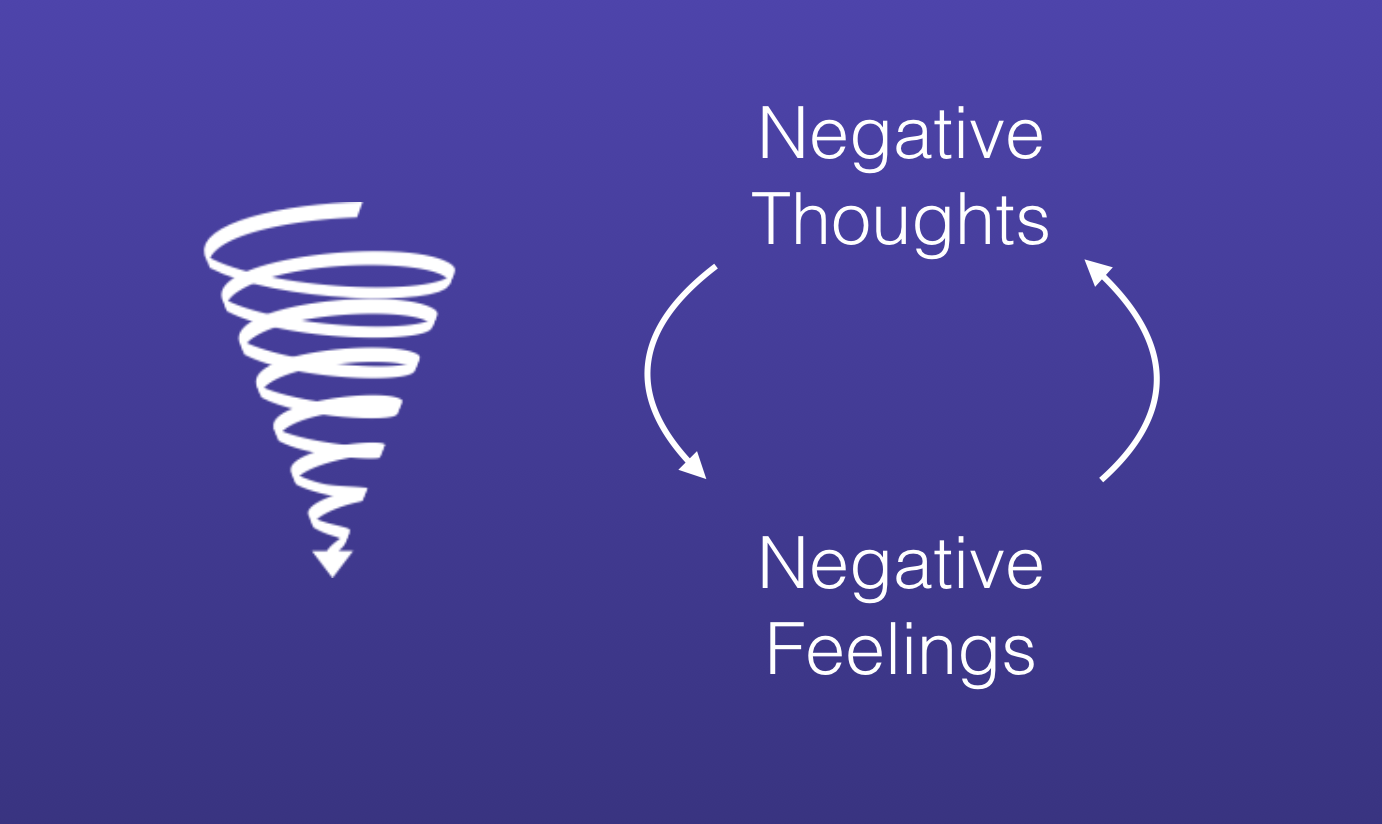

Sometimes these automatic or deliberate thoughts and feelings can cause a troublesome feedback loop – a “downward spiral”. A downward spiral is a feedback loop of negative thoughts, leading to negative feelings, leading to more negative thoughts, etc.

A downward spiral. Negative thoughts leading to negative feelings leading back to more negative thoughts.

A downward spiral. Negative thoughts leading to negative feelings leading back to more negative thoughts.

For example, that time when I stepped in a puddle on my way to a Meetup event. That made my already-bad mood even worse. I heard myself automatically think something like “I am stupid,” and that kicked off a downward spiral for me.

A downward spiral like this is not usually so useful. It manages to both make you feel worse AND distract you from focusing on things that are important. We generally want to avoid downward spirals.

If you effectively influence your mind, you can often control whether you let this happen to yourself or not. You will become more effective, think more clearly, and choose a better response more often.

Homework

- Think about times you wish you had behaved differently. Look out for opportunities where “debugging” could help you end up with a better outcome.

- Draw out the “IPO Model” from memory.

- Try explaining “inner vs outer brain” to a friend or coworker.

Read More

“Debugging Your Brain” is a 5-part series. Part 5 is still in progress and is not posted yet.

- “Part 1: Modeling” - When brain-debugging helps, and a model of how the brain works when debugging.

- “Part 2: Breakpoints” - How to get your mind into a state where you can debug: how to hit a breakpoint. Here you’ll investigate what the “inputs” to your system are.

- “Part 3: Processing Experiences” - Six concrete ways to deal with processing experiences more fully and effectively.

- “Part 4: Validation and Close Relationships” - How to effectively validate and support close friends.

- “Part 5: Thoughts” - You’ll learn about the 10 most common “maladaptive thought patterns” you’ll want to look out for and convert into “adaptive” thought patterns.

Find out more

Find out more